|

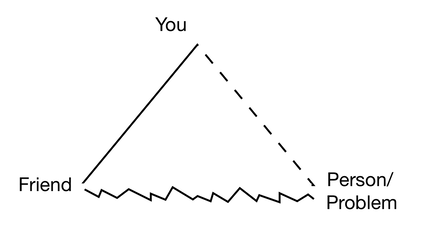

by Rev. Tres Adames, MDiv, BCPC A friend you've known for years comes to you for help. They are desperate, emotional, and ask you to intervene. Maybe it's a problem with their partner, a habit they are trying to kick, or a struggle with anxiety or depression. You care about your friend, so of course you want to help. But before you jump in, it might be time to step on the brakes. There is nothing wrong with wanting to support your friend, but make sure you don't get in over your head. There is a difference between helping your friend versus taking on their problem. This is hard especially for empathetic people. We want to pitch in and help out. Yet it creates more problems if we don't approach it the right way. Aren't We Supposed to Help Others? Those I work with in counseling will point to the Bible, mentioning that we should help other people. This is true—we are supposed to care about others and help them, but only when they cannot help themselves. The Bible not only stresses the importance of helping others, but also emphasizes the importance of taking personal responsibility. According to the words of the Apostle Paul: Brothers and sisters, if someone is caught in a sin, you who live by the Spirit should restore that person gently. But watch yourselves, or you also may be tempted. Carry each other’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ. If anyone thinks they are something when they are not, they deceive themselves. Each one should test their own actions. Then they can take pride in themselves alone, without comparing themselves to someone else, for each one should carry their own load" (Galatians 6:1-5, NIV). What is Paul saying here? He encourages the Galatians to "carry each others's burdens" but also that "each one should carry their own load." How is this possible? Aren't they the same thing? Not necessarily. In their book, Boundaries, Henry Cloud and John Townsend shed some light on the difference between a load and a burden: "The Greek word for burden means 'excess burdens,' or burdens that are so heavy that they weigh us down. These burdens are like boulders. They can crush us. We shouldn’t be expected to carry a boulder by ourselves! It would break our backs. We need help with the boulders — those times of crisis and tragedy in our lives. In contrast, the Greek word for load means 'cargo,' or 'the burden of daily toil.' This word describes the everyday things we all need to do. These loads are like knapsacks. Knapsacks are possible to carry. We are expected to carry our own" (Cloud & Townsend, 2017). We can help and be supportive, but we are not called to fix other people's problems or take responsibility for them. Paul is emphasizing the need for love and personal responsibility. In order to learn how to do this, let's dive deeper and explore this from the world of family systems theory. Don't Get Triangled! One of the most impactful books on relationships in the field of pastoral counseling is Generation to Generation by Edwin Friedman. In the book, Friedman describes what is known as an emotional triangle. According to Friedman: “The basic law of emotional triangles is that when any two parts of a system [this could be a family, a work environment, or a circle of friends] become uncomfortable with one another, they will ‘triangle in’ or focus upon a third person, or issue, as a way of stabilizing their own relationship with one another” (Friedman, 1985). Often, a third person is pulled into a triangle when two people in a relationship are in conflict with one another. To stabilize the relationship, another person is asked to help or may even be pulled into the situation by one or both people in the relationship. Sometimes the third person may intervene or “triangle” themselves into the unstable relationship out of desire to help. An example of an emotional triangle would be: 1) An adult man who is estranged from his adult brother 2) The brother 3) The parent who is asked to intervene or communicate on behalf of both. A part of an emotional triangle can also be a problem, such as an addictive habit or dysfunction. An example of a triangle involving a problem would be: 1) A person struggling with substance abuse 2) The substance abuse itself 3) An enabling partner. Let's take a look at this visually: Here you see the relationship between you and your friend indicated by a straight line. Your friend's struggling relationship with the other person (or problem) is represented by a jagged line. Notice that a broken line connects the third side of the triangle. Why? This is to indicate that there typically exists no control or real influence between you and the other person's relationship or problem. When any relationship is stuck, it is likely because a third person or issue has been interjected into the relationship. If you are the third wheel being introduced, the fact of the matter is that you have very little control over the outcome. If you try to fix the problem, you will only absorb the anxiety and stress from the whole situation. Sometimes, interfering can even produce the opposite effect. Attempting to reconcile two sparring partners may make them more distant or hostile. So what's the takeaway? Don't get triangled! Don't allow yourself to be put in the middle of the situation. So how can you help your friend who comes to you for support? Let's talk about a few healthy and more effective ways to influence change. 5 Effective Ways to be Supportive 1. Improve your relationship with both sides--Friedman notes that “We can only change the relationship to which we belong. Therefore, the way to bring change to the relationship of two others (and no one said it is easy) is to try to maintain a well-defined relationship with each, and to avoid the responsibility for their relationship with one another” (Friedman, 1985). Seek to be mature and get along with both sides. This might mean giving the benefit of the doubt to both persons in a conflicted relationship. If it concerns a friend struggling with addiction, work on your relationship with your friend and also work on your relationship with addiction itself—that is, learn more about addiction and how it works so you are more educated on how to respond. 2. Focus on the person, not the problem—Rather than getting caught up in solving the problem, encourage your friend's ability to take responsibility for it on their own. When the conversation drifts toward venting about the other person or problem, bring the focus of the discussion back to your friend. Ask how they are feeling and what's going on inside. 3. Ask questions, don't give answers—If your friend is insistent on talking about the problem, don't offer any solutions. Simply ask questions about how they plan to tackle the issue. This encourages them to strategize on their own rather than depending on you to solve their problem. 4. Be kind, but firm—Set boundaries with your friend as needed. If they keep calling or texting you, let them gently know that you aren't always available. Suggest other sources of support. Consider referring them to a local Christian counselor who specializes in the issue they are facing. 5. Remain self differentiated—Take care of yourself and acknowledge that this is not your problem—thankfully! Remain grounded, present, and non-anxious while still remaining connected as appropriate. Encourage them to seek God for wisdom. Offer to pray for them instead of being the only one they vent to. Besides, God wants us to talk to Him. May this be the situation that draws them closer to Him. Works Cited

Comments are closed.

|

Article Topics

All

Archives

July 2023

|

We're ready to help. Let's begin.

Peoria LocationInside State Farm

9299 W Olive Ave Ste 212 Peoria AZ 85345 |

Phoenix LocationInside CrossRoads UMC

7901 N Central Ave Phoenix AZ 85020 |

About |

Services |

EducationPrograms

ACPE Spiritual Care Specialist Pastoral Counseling Apprenticeship Deconstruction Course Free Grief Training Contact |

We're ready to help. Let's begin.

© 2024 Prism Counseling & Coaching. All Rights Reserved.

Christian DISC® is a registered trademark of Prism Counseling & Coaching.

Christian DISC® is a registered trademark of Prism Counseling & Coaching.